A man died on the road last week. He wasn’t speeding. He wasn’t careless. He was simply trying to pull out a tipper stuck in the mud, the same mud that had swallowed others before him along the Aizawl-Silchar stretch. The tipper rolled and crushed him to death.

There is something particularly tragic, almost comedic, about a government that blames the tipper for tripping, but never the potholes or the mud. That is how the state of our roads kills: not in one spectacular collapse, but through the slow attrition of neglect. Every tipper driver who drives through that route carries the weight of a system that has long ceased to care. When the tipper drivers blocked the highway to protest these dangerous conditions, the government’s response was not grief, but a predictable warning: a reminder that blocking a national highway is a punishable offence. Here lies the essence of our politics: a law that mourns its own inconvenience more than the death it helped produce. The roads are impassable, yet it is the tippers who are accused of obstruction. The wheel of legality turns smoothly, even as the real wheels sink deeper into the mud.

Power often reveals itself through what it refuses to hear. The government’s reaction to the tippers’ protest, its silence toward the cause, and its swift condemnation of the act of protest make this refusal visible. Instead of recognizing the suffering it has created, it diverts the blame toward those who make that suffering visible. The tippers are told they harm “innocent citizens” whose normal life largely depends upon the goods the tippers transport. But normal life, for the tippers, is already a disturbance. The danger of the road is their daily bread. Their protest does not create suffering; it reveals it. And what the state cannot tolerate is precisely revelation. Power, therefore, prefers silence, or better, circulation. It wants things to move: goods, people, obedience. Movement is its theology. So when the tippers simply had enough and stopped, they interrupted this sacred flow. They turned the state’s infrastructure of injustice against itself. Their protests exposed that the smoothness of normal life or governance was an illusion maintained by the constant endurance of those beneath it.

This pattern of denial repeats itself elsewhere, though in subtler forms, through the language of moral order and “public good.” Consider the Mizoram Prohibition of Beggary Bill that was recently passed: its ‘statement of objects and reasons’ suggests that “beggary is a social evil.” But whose evil, really, the economic conditions that necessitate one to beg, to ask for alms, or the act of begging itself? What those fifteen long pages of beggary “definitions,” “prohibitions,” and “punishments” can’t quite grasp about begging is its conditions: poverty, a failed welfare state, scarcity of gainful employment, especially for the disabled. The timing of the Bill was not incidental. The opening of the railway line soon followed, linking Bairabi to Sairang, and with it came official murmurs of fear: that beggars from outside, non-Mizo, poor, unassimilable, would arrive and disrupt the city’s imagined cleanliness. The fear was not of poverty itself, but of seeing it.

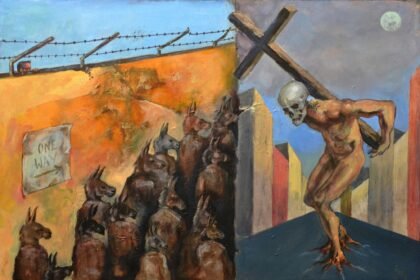

The beggar, like the tipper, is intolerable because he refuses invisibility. He unsettles the dream of a modern, orderly Mizoram by embodying the failure that modernity wishes to conceal. So the government moves to erase the image, not by addressing the poverty that produces it, but by outlawing its appearance. To prohibit begging is not to end destitution; it is to deny its visibility. And yet, the same state that fears the poor outsider invites the wealthy, loaded corporations like Patanjali. What did the Government do when that capital-colonizing company markets progress and profit when, in fact, it will choke the hills? It welcomed them with garlands and contracts. It is a revealing double standard: the poor outsider is the contaminant, the big and wealthy corporation the redeemer. What power fears, then, is not exploitation but exposure. The beggar and the tipper threaten precisely because they reveal what the government wants to hide: that progress has cracks, and those cracks have bodies inside them.

The late Theodore W. Adorno once wrote: “It is part of the mechanism of domination to forbid recognition of the suffering it produces.” That is what we see here, a machinery that forbids recognition. The government cannot afford to look at the suffering it creates because to see it would mean acknowledging responsibility. Instead, it criminalizes those who bear the marks of its neglect. Every prohibition, then, becomes a displacement: to forbid begging is easier than confronting why people beg; to ban alcohol and police drug addicts is easier than asking why despair and trauma drive people to abuse substances; to outlaw protest is easier than admitting that the road has collapsed. These gestures of prohibition form a moral theatre that conceals political decay. In such a decay, a child would do better than the existing political system because, unlike our leaders, her natural curiosity would not be afraid to ask the “whys” of issues.

I do not pit the tippers against the beggars or the alcoholics and drug addicts; their struggles differ, but I am simply intending to point out the obvious, that the silence surrounding them is the same. If the tipper’s death makes the news, it is because his labour feeds the economy; the beggar’s hunger does not, because he carries nothing the market can value. It is a cruel arithmetic of visibility, one that measures grief by utility. If the public displays solidarity toward his protest, it is because his suffering carries a degree of social weight. His body belongs to a visible economy: one that transports the nation’s goods and sustains its markets. When he blocks the road, the country trembles, not out of compassion, but out of dependency. The beggar, the alcoholic, or even the drug addict has no such leverage. Their existence is tolerated only as pathology, their suffering stripped of political value. Here lies the cruel hierarchy of recognition: the right to be heard depends on the extent to which one’s pain can disturb the machinery of profit and circulation. A tipper can interrupt it. A beggar cannot.

We are told that all citizens are equal before the law, but equality before the law is not equality before power. The law does not protect those who cannot afford to be seen. It merely confirms their disappearance. But beneath that hierarchy runs a single logic: the refusal to recognize the conditions that produce suffering. The government punishes symptoms because it fears the diagnosis. It does not want to know that the cracks in the road and the cracks in society spring from the same soil: neglect, greed, and the comfort of a power that has stopped listening.

To live under such governmentality, then, is to live within a vast theater of moral displacement. Every social failure is retold as an individual sin. Poverty becomes laziness, addiction becomes lack of self-restraint and weak will, and at times, simply spiritual corruption, and dissent becomes criminality. The state stands apart, pure and blameless, its hands folded like a priest’s, offering redemption through punishment. But this is not governance in any meaningful sense. It is a theology of order, where the divine word is “development” and the ritual sacrifice is those vulnerable subjects: workers, beggars, etc.

There is something almost perverse in how the state insists that it cares. It says: We ban begging because we love dignity. We ban liquor because we care for health. We police protests because we want peace. But each prohibition erases the condition that made the act necessary. In the end, the beggar is still hungry, the alcoholic still despairing, the tipper still stranded; only now they must suffer quietly, unseen, so that the surface of the state remains undisturbed. This is governance as anesthesia. It numbs not only the governed but also those who govern, until both sides mistake silence for stability.

One could almost admire the elegance of this machinery of domination. It functions not by brute repression and force but by converting every failure into a moral tale. The citizen learns to internalize the state’s voice and guilt, to scold himself before anyone else does. “If I cannot feed my family,” he thinks, “I must have been lazy.” “If I drink,” he whispers, “I must lack discipline.” “If the road is bad,” he says, “maybe the monsoon has not been kind to us.”

The genius of power is that it teaches its subjects to narrate their own domination as guilt. And when collective anger breaks through, as in the tippers’ blockade, the state invokes legality to restore the order of guilt. The protester becomes the criminal, the government the victim, the road the forgotten corpse. But something in these gestures reveals the deeper fragility of power itself. For all its talk of law and morality, the state depends on precisely those it disowns. The beggar’s existence testifies to the failure of its economy; the drunk exposes the loneliness of its progress; the tipper’s blockade uncovers the cracks in its infrastructure. They are not exceptions; they are the truth that the system cannot bear.

The state thus exists in a paradox: it must hide the suffering it produces, yet it needs that suffering to define its own virtue. The more poverty it creates, the more laws it passes to conceal it. The more despair it breeds, the more morality it preaches. Its power grows through the management of its own rot. If we take a step back and observe, we might see that this logic extends far beyond roads and prohibitions. It governs the treatment of refugees, too, those whose very displacement exposes the borders as wounds rather than (imaginary) lines. Refugees are made into the nation’s remainder, the necessary “outside” that defines the purity of the “inside.” Every time a refugee is blamed for crime, unemployment, or land, rent, and other price fluctuations of any kind, the state absolves itself of responsibility. The refugee becomes the living scapegoat for the contradictions of development and modernity: too visible to ignore, too alien to recognize.

Just as the beggar is criminalized for his poverty, the refugee is criminalized for his survival. And just as the tipper’s dissent is silenced in the name of law, the refugee’s body is policed in the name of security. The underlying movement is the same: the state maintains itself by designating zones of expendability, lives that can be governed, contained, or erased without moral consequence.

We often imagine that power is centralized, that it sits in the assembly, inside ministries, behind desks. But power is diffuse. It circulates through the moral codes, the bureaucratic gestures, the everyday acceptance of what counts as “normal.” It lives in the polite indifference that passes by a beggar without seeing him, in the casual irritation toward a protest that delays traffic and transportation of goods, and in the satisfaction of blaming refugees for the state’s unease. This diffusion is what makes power resilient; it does not need to coerce when it can convince. It does not need to punish when it can define what punishment means.

And so the road remains broken, not just the physical highway winding through the hills, but the moral and political road that connects suffering to accountability. It remains full of cracks through which the tipper falls and gets stuck, and full of dust that blinds the rest of us from seeing how deeply we depend on those who carry the nation’s weight. There will come a time, perhaps, when those who govern will discover that the road does not end where their jurisdiction ends. That the cries they refused to hear echo still in the valleys they paved over with legality. That the beggar’s bowl, the refugee’s camp, and the tipper’s blockade were never obstructions but mirrors, mirrors showing the nation its true face.

Until then, we must learn to listen to the pauses, to the stillness where power trembles: in the moment the tipper stops his engine, in the beggar who keeps returning to the same corner no law can cleanse, in the drunk who refuses the shame that is meant to silence him, in the drug addict who chooses to stay where society has left him. For it is there, in that refusal to move, that politics begins again — Politics as a resistance against power, not in the corridors of law, not in the sermons of morality, but in the stubborn insistence of those who have nothing left to lose except the right to be seen.

Today or tomorrow, the tippers will move again, or it may very well be the case that they have already started moving (the question concerning how quickly order is restored hardly matters), the beggars will disappear from sight, and the speeches of progress will echo through the hills. But every journey along the Aizawl-Silchar highway will still carry that one ghostly question beneath its wheels:

Who among us must die for the road to move?