In 2022, when my mother was diagnosed with a terminal illness, it would be the beginning of an introspective turn in my academic journey. Something about the startling nature of the life-changing event made me want to return to my roots and seek meaning and healing in the stories that I had once heard in conversations and whispers as a child. So, my dear friend Donskobar Junisha Khongwir, lovingly called June, and I began a project documenting the community oral history of Happy Valley, Shillong, where I had many happy childhood memories. I began my journey as an oral historian, and I’m often asked, ‘Why oral history and how does it intersect with the discipline you belong to, Communication?’ In this brief article, I explore these questions while contextualizing the need for fresh and imaginative approaches to make academics, particularly those focused on community, more inclusive and collaborative. I end by reflecting on my own positionality as a researcher in the work that I do.

Oral history as decolonial practice:

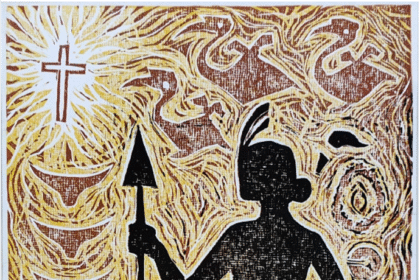

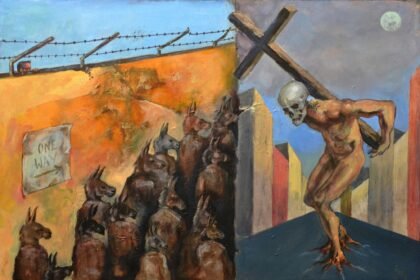

A colleague from the Oral History Association of India once remarked, with an unmissable sparkle in his eyes, that oral history is protest history. Although the first oral history book in India is indeed a literal protest history[1], he meant it more broadly in terms of historiography. Oral history is “history from below”[2] that facilitates the recording and preservation of marginalized, and in the case of our project, also discursively ghettoized, voices and their narratives, making it a progressive approach focusing on the agency of the narrators. The act of recording oral histories is also transgressive because it decentres the researcher, shifting the epistemic model from one that resembles extraction towards collaboration. Seminal works in the field have presented new vantage points from which to consider history. Two key works that I borrow from conceptually are Allesandro Portelli’s[3] reorientation of the focus from empirical accuracy towards the criticality of subjective meaning-making, and Michael Frisch’s “shared authority” [4]between researcher and narrator/ community, indicating a direct and consequential offsetting of the researcher’s traditional position. I also incorporate ideas from indigenous methods, such as the works of Robin Wall Kimmerer, Margaret Kovach, and Linda Tuhiwai Smith, which challenge dominant (primarily Western) approaches to research. Their work guides me in restoring epistemic authority to people who have been widely written about and spoken for in academia, grounding knowledge production and interpretation in their worldviews. To that end, oral history becomes a productive tool for decolonization.

Oral History and Communication:

My research in community history, from the Mizo in Happy Valley, Shillong, to my current work on the Mizo diaspora in the United States, has consistently revealed the centrality of orality in Mizo communication. Although we are adept at written and digital technologies, establishing trust and communication required for both projects necessitated my presence on-site, where I met with community members and collaboratively framed various aspects of the projects, including potential implications and outcomes. James Carey[5] offers a framework for the ritual view, emphasizing how communication plays a role in maintaining a culture over space and time through the representation of shared beliefs. Following Stuart Hall’s premise that representation is constitutive to an event[6], oral history empowers communities to self-represent, vitally redistributing interpretive power. Despite over a century of literacy, the Mizo still rely on oral traditions for meaning-making and communication. These traditions remain central to understanding how being Mizo is productive of various cultural continuities and changes, intersecting my work with a vital aspect of communication, which Carey calls “a symbolic process whereby reality is produced, maintained, repaired and transformed”.[7]

Lessons from Stories from the Valley:

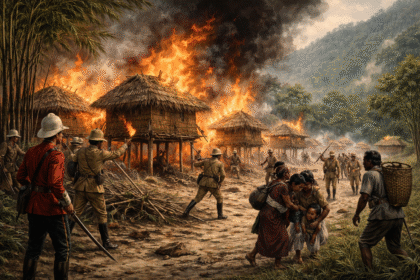

The Stories from the Valley project focused on the Mizo of Happy Valley and their community history. Over the course of a year, June and I met, laughed, cried, and shared meals with narrators. The locality, as it is called in Shillong, was formed partly due to the turbulent Rambuai (troubled/disturbed land) period in Mizoram. What began as a community history evolved into a fascinating exploration of how people coped with the hardships of displacement, serving as a lesson in resilience. We aimed to center their narratives and worked toward creating a meaningful keepsake for the community—a book co-written with them.

I conducted the interviews primarily in Mizo while June photographed the entire process, providing crucial visual context. Through photography, June added a complementary, interpretive mode of listening that settled the narratives, anchoring them within a tangible temporal and spatial framework. We discovered that the recounting of traumatic memories is often fragmentary [8], and allowing this form to spill onto the pages of the book was powerful and moving. The way the interviews are presented in the book allows for new imaginings of how narratives can unfold. Our intention was always to provoke good questions, rather than provide easy answers. The flexibility of the oral history approach also allowed for the narratives to emerge in unexpected ways, often becoming pleasant, if poignant, surprises.

Keeping in mind the politics of translation [9], we decided to publish the book bilingually in Mizo and English to ensure accessibility for our older narrators, many of whom were proficient readers only in Mizo. In a gesture of shared ownership, a few community narrators launched the book at the 2023 Shillong Literature Festival. We also plan a local exhibition to further encourage community engagement with our collaborative work. Although this has been delayed due to time constraints, it will take place, inviting people into dialogue. As we have noted elsewhere, this project was never meant to be a closed circuit; we welcome productive friction as we expand Rambuai Literature into the narrow lanes of Happy Valley.

The most rewarding aspect of the entire project was the palpable excitement from our narrators and the broader community. Books were shared, stories swapped, and photos giggled over. We received a plethora of responses from a wide range of readers —young and old, as well as those who only looked at the photographs. An unforgettable comment we received about the book was that “it reads like a documentary”. We are pleased that the major outcomes of the project were received with generosity by members of the community. Another unexpected but welcome outcome was that the project became a catalyst for inter-community dialogue. Through honest and organic recollections, we gained insight into the complex interplay of tensions and solidarity across the different communities that continue to inhabit Happy Valley.

My positionality as a researcher:

Being a child both of diaspora, and of mixed race, has always problematised my sense of belonging-ness. For instance, when I conduct fieldwork and participate in community, I am Mizo. However, when I appear on a televised interview and stumble over a few Mizo words or use English words, I am considered not Mizo enough. This has convinced me that being Mizo is in a constant state of flux, influenced by several factors. It also made me acutely aware of my positionality as a researcher. Being diasporic Mizo helps me understand Mizo-ness and related issues in the diasporic context. This became even more stark when writing an academic paper based on the project’s findings. Rambuai was a terrible chapter for many, followed by a time of rebuilding. However, as a third-generation diasporic Mizo, I understood the distinct struggle of the Mizo community in Happy Valley. For them, the challenge of rebuilding was compounded by relocation to a new place, where the languages spoken, customs, and the daily rhythms of life were foreign, layering the trauma of displacement over the pain of loss. The unique advantage of understanding both the language and worldview of my narrators helped me incorporate uniquely Mizo perspectives into the analysis. My experience has led me to believe that projects on communities benefit greatly when at least one primary researcher is from the community.

Lived experiences hold a wealth of knowledge and wisdom, often overlooked in favour of an archival logic that objectifies communities by treating them as anthropological subjects of study. The personal is political, and also historiographical, for marginalized communities who construct and frame their histories through personal experiences. Excluding these narratives from broader public discourse is akin to epistemic violence, resulting in a fractured and incomplete record. It has been humbling to participate in the process of co-creating narratives. I have a newfound joy in returning to traditional Mizo wisdom, its modes of knowledge production and transmission, and my scholarship is spurred by the urgency of preserving them, not as static artifacts, but in making them legible within contemporary frameworks relevant for future generations.

Note: This is not intended to be an academic article; however, I have included readings as footnotes and some author names that may be helpful in further exploration of specific topics.

[1] Stree Shakti Sanghatana, We Were Making History: Life Stories of Women in the Telangana People’s Struggle (New Delhi: Kali for Women, 1989).

[2] See chapter History and the Community in Paul Thompson, The Voice of the Past: Oral History, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

[3] Alessandro Portelli, The death of Luigi Trastulli and other stories: Form and meaning in

oral history (State University of New York Press, 1991).

[4] Michael Frisch, A Shared Authority: Essays on the Craft and Meaning of Oral and Public

History (State University of New York Press, 1990).

[5] James W. Carey, Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society, rev. ed. (New York: Routledge, 2009).

[6] Stuart Hall, ed., Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (London: Sage Publications, 1997). See his introductory chapter.

[7] Carey, Communication as Culture, 19.

[8] Bessel van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of

Trauma (Viking, Penguin Publishing Group, 2014) explains how traumatic experiences

can alter brain function, nervous system regulation, and even posture and immune

response.

[9] Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, The Language of Languages: Reflections on Translation (Seagull

Books, 2023)