I don’t care for Hnahsin Kut

Chapchar Kut or any other Kut

If our clothes exoticized

And our culture mysticized

Restraining us and our ways of life

I don’t care for them at all

There is no Zo Nun Mawi in it.

I don’t care for churches

If there is Christian infighting

Or denomination championing

No spirit of crusaders ever holy

Just for their glories solely

I don’t care for it at all

There is no Zo Nun Mawi I know

I don’t care for governments policies

“To uplift the poor” they lied

Whether it is Mau of richness or

Sawhthing of prosperity – promised.

If it’s empty promises by deceitful politicians

I don’t care for it at all

There is no Zo Nun Mawi D-A-H in the Act.

I don’t care for law enforcers

Or civil society organizations

If a widow’s son is beaten to death

And her house stoned to dust

Stoned first by he with sin I don’t care for them at all

If there is no Zo Nun Mawi in their deed

I don’t care for the Silent City

If bribes are taken silently

By those who worshiped the horned one

Silent ’cause no one voice the truth

Afraid to stand, afraid of “mi pawi sawi”

I don’t care for all of it

There is no Zo Nun Mawi in being voiceless.

I don’t care for even Zo Nun Mawi itself

If it’s constrained just for a single group,

If it cannot include all the people of Zo

All the Sap and Vai, and he, him, she, her, they them for that matter,

I don’t care for it if it cannot include all.

Why not let Zo Nun Mawi be a way of life for all?

A holistic inclusive altruistic noble way of life.

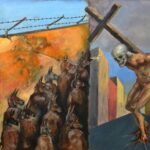

This poem is a self-introspection and denouncement of cultures around the poet, and a reclamation of what the poet calls “Zo Nun Mawi”. Festivals are first pointed at, Hnahsin, much like Anthurium festival, a celebration of exotic flowers as festivals, even the legitimate festivals like Chapchar kut did not get spared. With every verse the poet gives a reason as to why they do not care for it. Clothes, cultural apparel becoming costumes, exoticized, worn for the awe and wonder of outside eyes. At the end of the first verse the poet mentions “Zo Nun Mawi” an ethic, and champions it and laments in its absence in every ending of a verse.

The second verse goes after churches, commenting on the Christian infighting that they see. Denomination hierarchy and minorities trampled up. Holy crusades launched against enemies physical and spiritual only for the glory of the people waging it.

The poem gets topical in the third verse, mentioning upliftment schemes and projects that the government has failed the people with. Mau – Bamboo, sawhthing – ginger, mocking the politicians of their empty promises in how they sold their schemes. Further, it mentions law enforcers and civil society organizations, denouncing them again, “if a widow’s son is beaten to death and her house stoned to dust”, not just a single event, the poem highlights how the anger of the mob and authorities have often inflicted violence upon those below them.

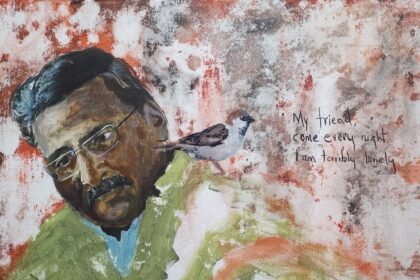

In the fourth verse, the poem again accuses those who take bribes silently in the Silent City, accusing them of worshipping the devil, the horned one, Mammon. Explaining why the Silent City is silent, the poem leads the readers towards how people refrain from criticizing because of “mi pawi sawi”, to be afraid of offending someone.

The last verse addresses the “Zo Nun mawi” mentioned, announcing that they do not care for it, IF, it is just for one group. Here, the poem expands beyond narrow nomenclature and nationalisms and invokes a wider lens of Zo people, going further to include even the people we deemed outsiders and introduces gender inclusion as well. In the last lines, the poem explains what “Zo Nun Mawi” could be ‘a way of life for all. A holistic inclusive altruistic noble way of life.’