My voice may sound a bit strange

seem to be singing off-key

as I go for minor modes,

not being majoritarian

My tribe you dub “subaltern” –

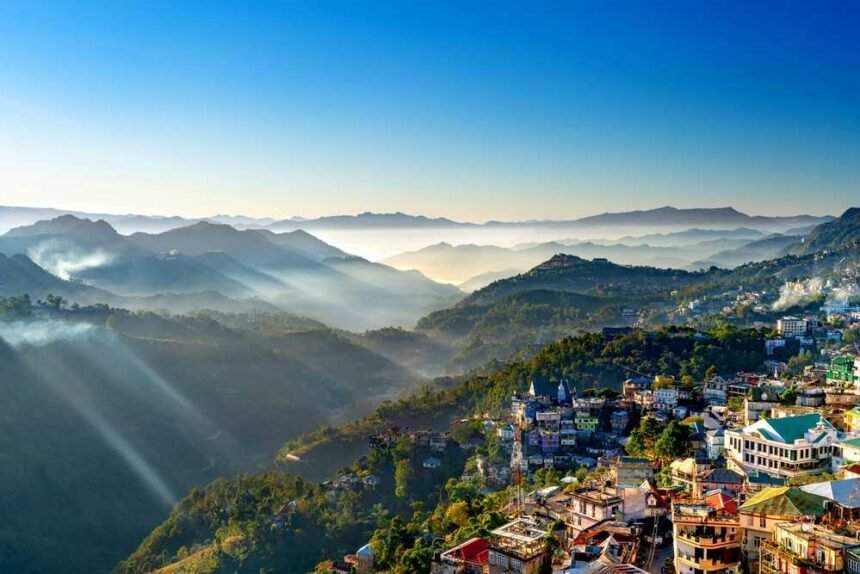

we call ourselves highlanders –

live on sharp rugged hills

Our voice buried many years

is now beginning to rise

We’re rich in tales and legends

stored in our collective-conscious

but have little written history

since the only manuscript we had

on leather scroll, was kept unguarded

and stolen away.

Nevertheless, we are part of

universal brotherhood;

the sky and earth are ours

as well as yours.

The poem is a critical introspection on identity, beautifully using the tunes – off-key and minor, to the negation of the majoritarian. This can be a play on how off-key and strange their tunes and melodies are compared to colonial rigid solfa and melodies, positioning the poet and the poem into a confrontation with the majoritarian coercion and violence.

This goes deeper with the second verse, calling out the use of “subaltern” while they call themselves “highlanders”. This is a reference to the term “subaltern” often spoken of by academics and intellectuals, coined by Gramsci who used the word to define “the natives” in an imperial colony. The poet intentionally uses how they have been dubbed “subaltern” and mentions just after how they themselves know themselves as “Highlanders”, this resists the submission towards being a minority.

The poem is an experience, a declaration of the tides rising. The second verse takes us to understand how oral cultures have rich tales and worldbuilding, and yet little is written about them, mentioning the tragedy(?) of losing the only script they had in their tales – how a dog stole the only written leather scroll away. This verse champions orality, the diverse and changing narratives that are woven by storytellers and songwriters, and the common man. How rich the culture is without the reinforcement of written texts.

The poem intentionally uses “My”, “I” and “We”, where the personal and collective become one, and there is no way to find out if there is a difference. The ending reconciles the “You” and “They” mentioned, proclaiming a universal brotherhood, perhaps of an internationalist solidarity with all humans and the right to nature. The climactic ending resists narrow nationalisms and nation-state politics and fights against things that can hamper solidarity – proclaiming that nature belongs to all of the people.