The monsoon session of the Mizoram Legislative Assembly this year has been fraught with controversy, with the ruling Zoram People’s Movement (ZPM) endorsing a bill they had once labelled “dangerous” before coming to power.[1] On 28 August 2025, the Assembly resolved to extend the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Act, 2023, to the State. This legislation has drawn nationwide criticism for its sweeping changes to the original 1980 Act—most notably the exemption it grants for diverting forest land within 100 kilometres of international borders in the name of “national interest” and “security.” In practice, this provision removes much of the Northeast, including Mizoram, from established safeguards. Critics argue that the Amendment undermines ecological protections affirmed under the Godavarman principle, weakens the standing of community-managed and unrecorded forests, and sidelines gram sabhas and tribal rights guaranteed under the Forest Rights Act, 2006. By adopting it, Mizoram now finds itself drawn into wider national debates on environmental governance, federalism, indigenous autonomy, and the uneasy balance between security priorities and ecological stewardship.

Outside the Assembly walls, the monsoon season presents another layer of contradictions. Mizoram’s famed azure hills—once poetically celebrated as the “land of blue mountains”—are increasingly scarred by landslides, their slopes now covered in blue silpauline sheets that ironically transform them into literal blue mountains. This fragile terrain reflects the difficult choices before the State. Across the Northeast, the region is being reframed as a frontier for extractive development—palm oil plantations, mega-infrastructure, and connectivity projects—advanced under the rhetoric of “regional integration.” In this way, the debates taking place inside the Assembly find their echo in the altered landscape outside: both reveal how Mizoram, and the Northeast more broadly, stand at a crossroads of ecological vulnerability and the pressures of developmental expansion.

Beyond questions of policy, however, I see this moment as a direct challenge to our sense of identity and history. To make this argument, I turn to art and the politics of visual representation as a lens for rethinking how history and identity are imagined. I was recently invited to speak on the politics of history, memory, and identity, a discussion that left me with further questions about how we see ourselves and our past. My reflections here are shaped by the idea that the reconstruction of identity and history has often been left to artists—particularly in societies like ours, which lack an extensive visual archive in the form of ethnographic photographs or abundant anthropological records.

The dominance of the visual in shaping truth is evident. Visual evidence is often regarded as more concrete than oral accounts. In our judicial system, for example, photographs and documents are treated as more reliable than testimonies. The familiar saying “seeing is believing” continues to guide how we construct and reconstruct both history and identity. Visual markers of Mizo identity—such as textiles like chawilukhum (or vakiria), kawrchei, thangchhuah kawr, and khumbeu—have become central, while intangible cultural values such as tlawmngaihna have been pushed to the margins. The recent state policy of dedicating a day to celebrate identity through clothing is symptomatic of this emphasis on the visual as a primary marker of who we are. Yet it is equally important to look at how more modern notions of identity have been shaped.

In her book Being Mizo, Joy Pachuau shows how colonial framings—through Western medicine, formal education, and above all, Christianity—shaped contemporary Mizo identity, such that today we often see ourselves as inherently “Mizo Christians.” Over time, this intertwining of Christianity and Mizo-ness has produced an identity marked by colonial influence. Unlike elsewhere, colonial rule in the Lushai Hills (now Mizoram) is seldom remembered in wholly negative terms. Local expressions capture this perception: thim ata engah (“from darkness to light”), Pathian zawnchhuah ram (“a land sought out by God”), and sap-in min awp lai—where awp refers to a hen incubating her chicks—all reinforce the view of colonial presence as nurturing, even providential, as Pachuau notes.

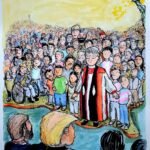

Artists have long engaged with this history. Often, they take on the role of historian or ethnographer, reconstructing the past visually. This compulsion to convert history into an image is itself revealing. In one of Tlangrokhuma’s so-called “historical paintings,” he depicts the commemorative encounter between Bengkhuaia, chief of Sailam, and British officer Tom Lewin on the banks of the Lau River—an episode that has become central in Mizo collective memory.

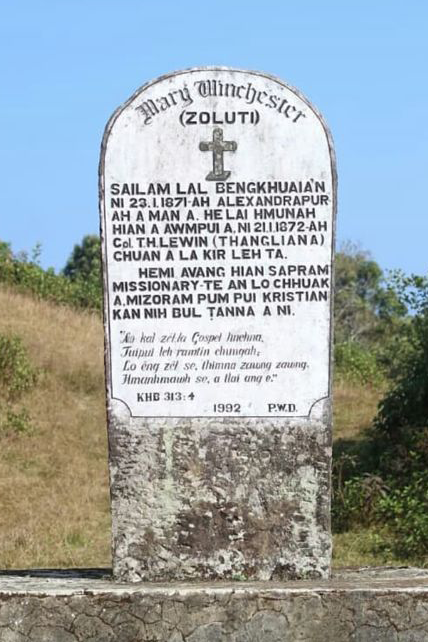

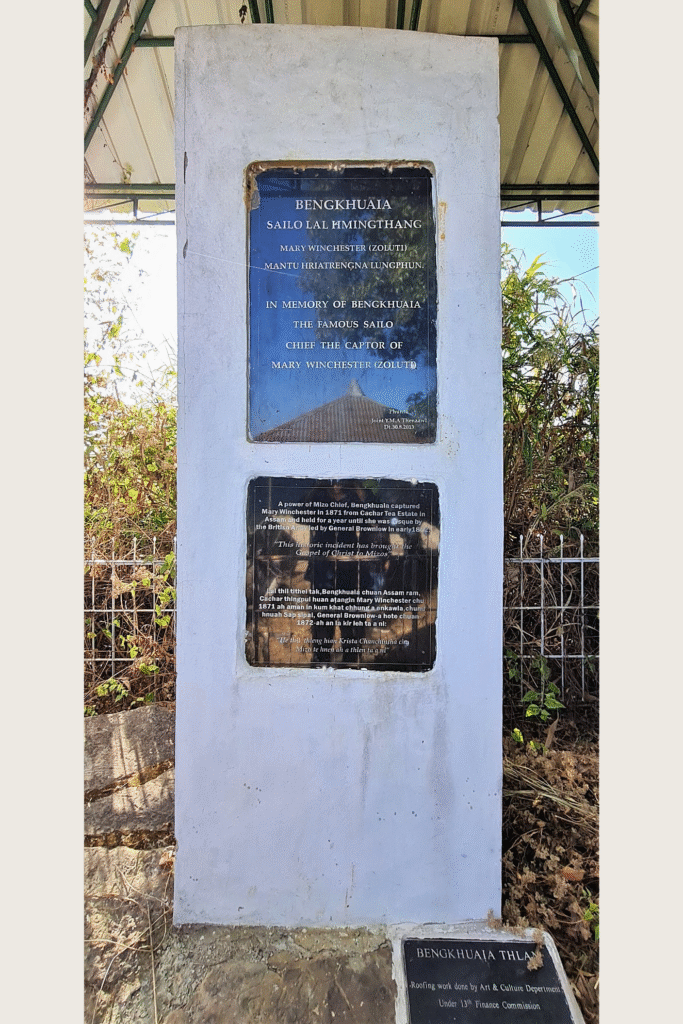

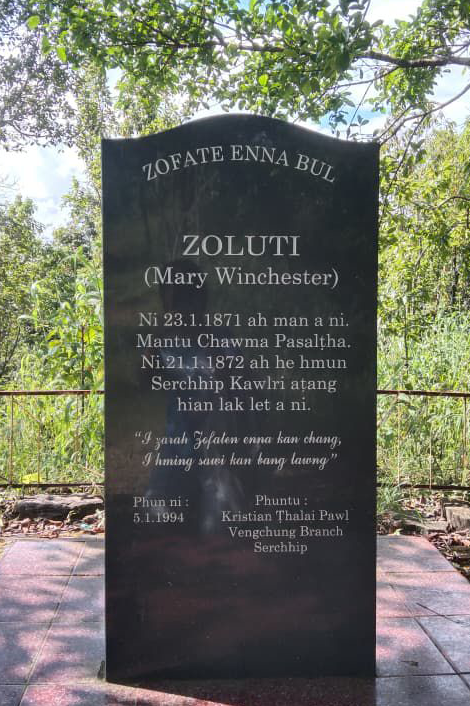

The story of British annexation, remembered as vai len, revolves around Bengkhuaia’s raid on the Alexandrapur tea estate and the capture of Mary Winchester (Zoluti). This moment is often presented as the turning point for Christianity’s entry into the Lushai Hills. Commemorative stones across Mizoram reinforce this link between Bengkhuaia, Zoluti, and the spread of Christianity. In Tlangrokhuma’s painting, the scene is rendered with overtly Christian symbolism: the sky opens, divine light falls upon the British officer, and the figures appear almost like angelic witnesses in a sacred drama.

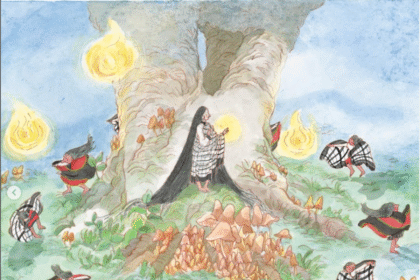

Another of Tlangrokhuma’s works, Great Warriors (also known as Bengkhuaia’s Men), tells a different story. It portrays the chief’s warriors not as violent or “savage,” as colonial depictions often did, but as ordinary men resting, free of aggression. Without context, it would be difficult to associate this image with the Alexandrapur raid or Mary Winchester’s capture. Yet through such visual renderings, Bengkhuaia is firmly positioned as the central figure in the narrative of Christianity’s arrival.

But beyond this validation of Bengkhuaia as protagonist in the making of “Christian Mizo identity,” we need to rethink the raids themselves. From the Mizo perspective, such raids were responses to the encroachment of British plantations onto their land. The crucial hunting and resource ground for the Mizos, were also coveted by the British to expand their tea estate. As the British expanded, chiefs perceived a threat to their territories and responded with aggression. R. Zamawia, in Zofate Zinkawngah, recounts how Mizos, often described as peace-loving, were forced into raids as their only mode of negotiation, limited by weak bargaining power and language barriers. He cites Edgar, Governor of Cachar, who recorded chiefs warning: “You have cleared the hunting grounds of our young men… stop clearing the forest.” Yet British expansion continued, provoking Bengkhuaia’s men to retaliate through raids.

Christianity’s arrival did bring new modalities of modernity, often at odds with older cultural practices, transforming Mizo identity in profound ways. But how do we remember this history in ways not confined to anthropocentric or visual frames?

The challenge is to imagine history, culture, and memory beyond spectacle and beyond purely human-centered narratives. For indigenous cultures, identity has always been anchored in more-than-human relations, especially with the land. This relationship is not merely symbolic but deeply lived, shaping belonging across generations. Today, however, the dominant idea of “development” increasingly severs this bond. What is lost is not only ecology but also the memory and identity once inseparable from it.

To the British, Bengkhuaia’s men were raiders driven by greed; to the Mizos, they were guardians of land and identity. Some scholars now interpret their actions as ecological resistance[2]—an insistence that forests and territories were not expendable for tea or profit.

In the end, what we call history, memory, or resistance is always contingent—framed by who tells the story and from where. Art, in this sense, becomes a space where these frames are contested, where silences can be broken, and where erased voices return. To resist erasure is not simply to preserve the past but to reframe memory in ways that remain alive, critical, and responsive to the urgencies of our present.

[1] When the Bill was first introduced in 2023, the Zoram People’s Movement (ZPM)—now the ruling party—strongly opposed it. The current Chief Minister himself was visibly present at protests, denouncing the Bill as a threat to Mizoram’s ecological and community rights.

[2] Dr. David C. Vanlalfakawma often remarked that this might have been the earliest ecological movement in India, predating even the Chipko movement.